Urartu: Who Were The Fortress Kings of Ancient Armenia?

Urartu (also known as the Kingdom of Van or Ararat) was one of the most powerful kingdoms of the ancient Near East during the Iron Age.

By: Robbie M. | Historic Mysteries

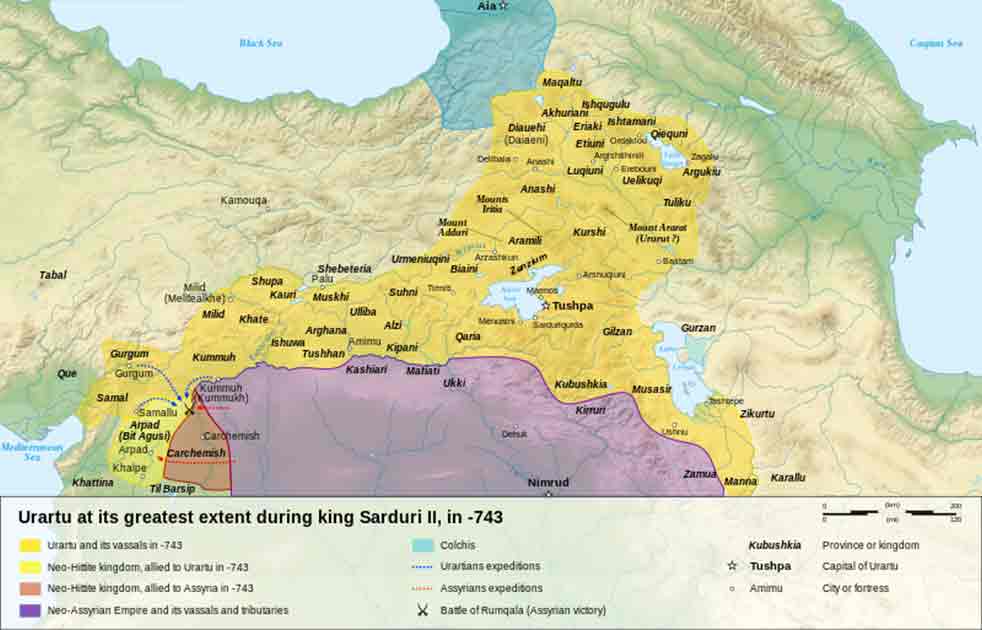

Hidden deep within the rugged landscapes of the ancient Near East, there once was a kingdom known for its power and its innovation, a kingdom that is now long-forgotten. The Kingdom of Urartu ruled this mountainous land from the 9th to the 6th centuries BC, thriving in the region encompassing present-day Türkiye, Armenia, and Iran.

Urartu left an indelible mark on the tapestry of antiquity. These fortress kings were conquerors, possessed on engineering genius, yet little is remembered of them today. Who were these ancient Armenians, and how did they fall?

A Force to Be Reckoned With

The kingdom of Urartu is believed to have appeared in the 9th century BC, carved out of the rugged terrain of the Armenian Highlands before growing to swallow up surrounding regions. Founded on the banks of Lake Van, Urartu’s origins are steeped in the movements of various Indo-European and indigenous peoples in the region.

Scholars theorize that Urartu likely evolved from the amalgamation of local tribes and the influx of newcomers, possibly including migrants from the ancient kingdom of Ararat. But wherever they came from, they carved themselves a kingdom.

Urartu’s rise to prominence was fuelled by its strategic location and the ingenuity of its people. Renowned for its mastery of fortress construction, the kingdom’s citadels served as both defensive bastions and administrative centres.

Perched atop rocky outcrops and steep hillsides, these imposing fortifications, including the famous fortress of Van (Tushpa), displayed Urartu’s architectural prowess and military might, earning the kingdom a reputation for impregnability.

As Urartu expanded its influence, its territorial reach grew, encompassing vast swathes of land stretching from the southern shores of Lake Van to the plains of northern Mesopotamia. This expansion was facilitated by a combination of military conquests and strategic alliances, with Urartian rulers consolidating their power through a network of vassal states and client kingdoms.

Urartu’s economy flourished on the fertile lands of the Armenian Highlands, sustained by a sophisticated network of irrigation canals and reservoirs. The kingdom’s engineers devised brilliant methods to harness water resources, enabling intensive agriculture and supporting a burgeoning population.

Urartu became famous for its agricultural produce, which included grains, fruits, and livestock, contributing to the kingdom’s prosperity and economic stability. It seemed that they would build themselves a paradise out of their wild lands, hidden in the mountains.

In addition to agriculture, Urartu engaged in trade with neighbouring states, exporting commodities such as metals, textiles, and luxury goods. This trade network fostered cultural exchange and facilitated the flow of wealth into Urartu, further enhancing its status as a regional power.

Collapse of The Fortress Kingdom

Urartu’s dominance in the ancient Near East endured for several centuries, reaching its zenith in the 8th century BC under the rule of King Sarduri I and his successors. During this period of expansion and prosperity, Urartu emerged as a formidable power, rivaling the mighty Assyrian Empire and exerting influence over vast territories in the region.

However, Urartu’s supremacy was not destined to last. The kingdom faced numerous challenges, including external invasions, internal unrest, and geopolitical shifts. In the late 8th and early 7th centuries BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire, under the leadership of kings such as Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II, launched campaigns to assert control over the lands once held by Urartu.

Despite continued efforts to resist Assyrian aggression, Urartu gradually succumbed to the overwhelming military might of its adversaries. The Assyrians, infamous for their military prowess and strategic brilliance, proved to be too much for the Urartians and besieged their cities, sacked fortresses, and subjugated vassal states, weakening Urartu’s grip on its territories.

The decline of Urartu accelerated in the 7th century BC, as successive Assyrian campaigns dealt severe blows to the kingdom’s power and prestige. In 734 BC, King Tiglath-Pileser III launched a devastating assault on Urartu, capturing its capital of Tushpa (Van) and imposing tribute on its rulers. Subsequent Assyrian kings continued to exploit Urartu’s weakened state, further eroding its hold on its territories, and weakening its influence in the region.

By the late 7th century BC, Urartu had been reduced to a shadow of its former glory. In 612 BC, the final blow came when the Assyrians, under the leadership of King Sinsharishkun, razed the Urartian capital of Tushpa to the ground, effectively bringing an end to the kingdom of Urartu.

What Remains Today?

Urartu was long forgotten, but that doesn’t mean traces of it can’t be found in the cultural heritage of the Armenian highlands, reminders of a once-mighty civilization. Of course, the most iconic remnants of this civilization are its magnificent fortresses, many of which still dot the rugged terrain. They remain proof of the Urartian civilization’s mastery of engineering, architectural prowess, and military ingenuity.

Of these fortresses, the most famous is the citadel of Van, once known as Tushpa. Located atop a rocky promontory overlooking Lake Van, the ruins of Van Fortress evoke the grandeur of Urartu’s imperial capital and offer visitors a glimpse into the kingdom’s glorious past. The fortress features massive stone walls, imposing gateways, and intricate architectural details, attesting to the craftsmanship of Urartian builders.

Other Urartian citadels have also survived, in one form or another. Cavustepe, Bastam, and Erebuni have all survived the ravages of time, albeit some more than others. These archaeological sites provide valuable insights into Urartu’s urban planning, defensive strategies, and social organization, offering archaeologists and historians a treasure trove of information to unravel the mysteries of this ancient civilization.

Alongside these fortresses, Urartu’s legacy survives in its inscriptions, remaining artworks, and the numerous artefacts left behind and scattered across the region. Inscribed stelae, clay tablets, and monumental reliefs adorned with intricate designs and inscriptions in the Urartian language provide invaluable clues to understanding the culture, religion, and history of the kingdom.

Today, ongoing archaeological excavations and research efforts continue to shed light on Urartu’s enigmatic past, unraveling its secrets and enriching our understanding of ancient Near Eastern civilizations. Museums in Armenia and Türkiye display artefacts from Urartian sites, allowing visitors to appreciate the artistic achievements and technological innovations of this remarkable civilization.

Today only the story remains, one of resilience, innovation, and cultural richness. Emerging from the rugged landscapes of the Armenian Highlands in the early 9th century BC, Urartu thrived as a dominant power in the ancient Near East, renowned for its formidable fortresses, advanced irrigation systems, and vibrant culture.

For centuries, Urartu stood as a bulwark against external threats and a beacon of civilization in the region. Its citadels, perched atop rocky outcrops and steep hillsides, symbolized the kingdom’s military might and architectural prowess, while its sophisticated irrigation networks sustained a flourishing agricultural economy.

However, like all civilizations that came before and after it, the glory of Urartu was not destined to last. In the face of relentless Assyrian aggression and internal challenges, the kingdom gradually declined, ultimately succumbing to the ravages of conquest, and time.

* * *

NEXT UP!

This Ancient Maya City Was Hidden In The Jungle For More Than 1,000 Years

Researchers from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have discovered the remains of a centuries-old Maya city in the Balamkú ecological reserve on the Yucatán Peninsula.

In a statement, lead archaeologist Ivan Šprajc says the settlement probably served as an important regional centre during the Maya Classic period, which spanned 250 to 1000 C.E. The team named the newly discovered ruins Ocomtún—“stone column” in Yucatec Mayan—in honour of the many columns found at the site.

“The biggest surprise turned out to be the site located on a ‘peninsula’ of high ground, surrounded by extensive wetlands,” says Šprajc in the statement, per Google Translate. “Its monumental nucleus covers more than [123 acres] and has various large buildings, including several pyramidal structures [nearly 50 feet] high.”

* * *

READ MORE: This Could Be The Earliest Evidence of A 260-Day Maya Calendar Ever Found

Intresting! Were The Mayans Visited by Ancient Astronauts?

Telegram: Stay connected and get the latest updates by following us on Telegram!

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Collective Spark Story please let us know below in the comment section.