Morphine, Santa Claus, And Nazis: The Secret History of Coca-Cola

What the Infamous company doesn’t want you to know!

By Tesla Telegraph | Guest Post

On the evening of April 16, 1865, Union and Confederate cavalry clashed over a bridge in Columbus, Georgia, in what was arguably the last battle of the U.S. Civil War. During the fight, a Confederate colonel named John Pemberton took a slashing saber wound to the chest and had to be carried away from the fight.

Believe it or not, this set of facts is the basis for why, today, you clip coupons before a shopping trip, why every vertical surface in the world is plastered with advertisements, and why children believe in Santa Claus.

Coca-Cola, the brand John Pemberton went on to found, has taken over the world. Interbrand, the authority on brand names and their value, lists Coca-Cola as the world’s third most valuable brand (behind Apple and Google). Its total assets equal about $90 billion (significantly more than Pepsi and Nike combined).

Moreover, Coca-Cola has grown into one of a select few brands that practically act as overseas ambassadors of the United States itself. Coca-Cola is so closely associated with American culture that the country’s cultural imperialism if often referred to as “Coca-Colonization.”

But what made Coca-Cola the symbol of America that it is today? Where did it start, how did it grow, and why is its logo probably more well-known than the American flag in all but two countries (Cuba and North Korea) on Earth today? It all started with that stroke of the saber that so nearly killed John Pemberton…

Coca-Cola’s History: Morphine & Cocaine

John Pemberton was dragged off the battlefield at Columbus with what was expected to be a mortal injury. The slashing saber had cut him deeply, and he was bleeding from a huge wound. Unconcerned about long-term side-effects, his doctors gave him a great deal of morphine to ease what they thought might be his last few hours.

The morphine treatment continued as Pemberton unexpectedly rallied and began to recover. But, like many Civil War veterans, he became dependent on the painkiller, even going so far as to start a pharmacy in Atlanta after the war to ensure a steady supply of his drug.

After about a decade, with his daily opiate habit taking its toll, Pemberton started looking for a cure. This was at a time (the 1870s) when medicine was barely scientific by today’s standards, and most “cures” for various ills were “patent medicines” that were virtually indistinguishable from exotic liqueurs.

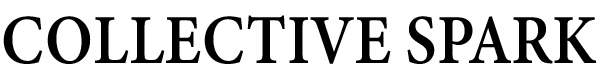

Pemberton had heard good things about coca wine, an admixture of wine and cocaine which was all the rage in France, and resolved to try it out.

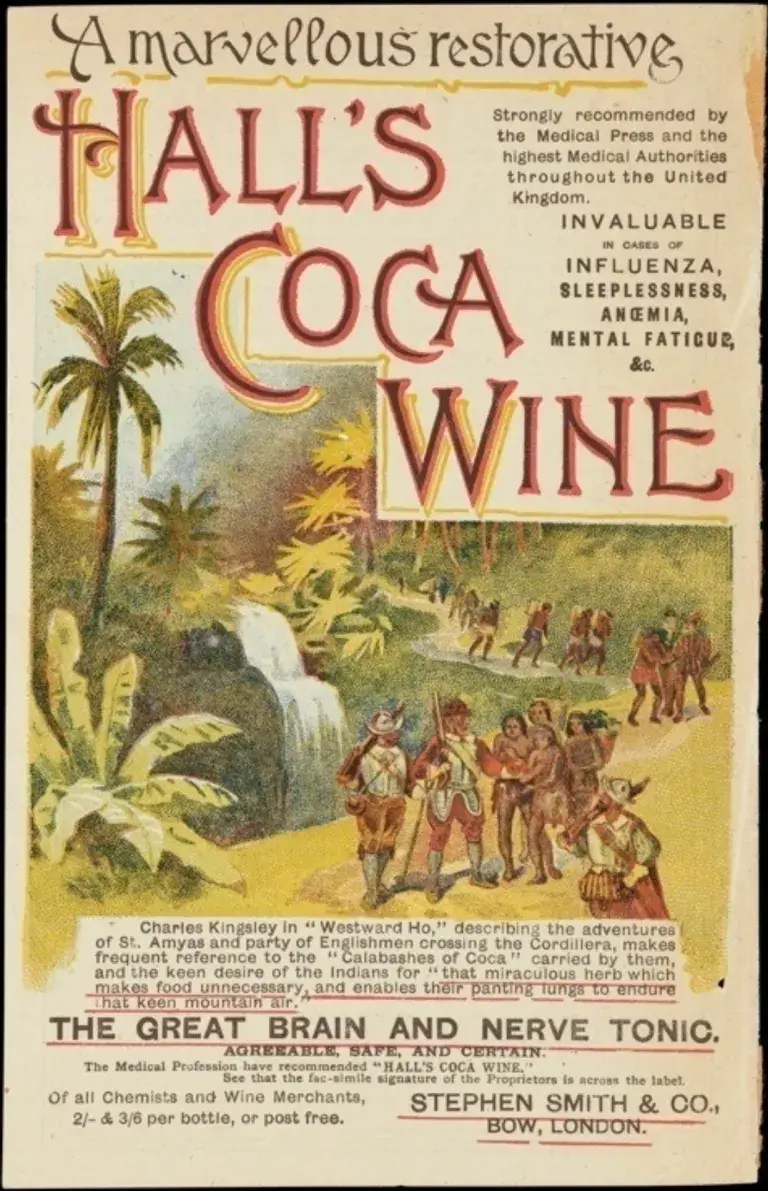

His first product, Pemberton’s French Wine Coca Nerve Tonic, was a strong shot of alcohol mixed with cocaine and marketed as a cure for a long list of ailments, including opiate addiction, upset stomach, neurasthenia, chronic headaches, and erectile dysfunction. The drink was whipped up in batches of thick syrup and delivered to pharmacies, where it could be mixed with soda water and dispensed by trained professionals.

However, disaster threatened Pemberton’s new venture when, in 1886, prohibition fever swept over his part of Georgia and halted the production and sale of alcohol.

Cocaine, however, was still totally fine. Pemberton reformulated his product into a non-alcoholic beverage and kept right on selling it — although, by 1888, the recipe contained only around nine milligrams of cocaine, which is about one-tenth the usual recreational dose.

Interestingly, though no Coke product has contained cocaine since 1903, one of Coke’s partners – the Stepan Company of New Jersey – retains the only active federal license to import and process coca leaves (from which cocaine is made).

That process produces raw cocaine, which is shipped to the only pharmaceutical company in America that’s licensed to handle it (Mallinckrodt), with the spent leaves then used to produce a flavouring agent that’s still employed in the top-secret recipe for Coca-Cola.

But even more than that highly sought-after recipe, the production-sales-distribution network Pemberton set up right off the bat is probably the single biggest factor in Coca-Cola’s early, and continued, success. Pemberton didn’t actually invest in facilities or distribution — instead, he made the syrup at his own plant, then shipped it out to contractors and affiliates who could mix it and sell it how they liked.

This system created a very flexible arrangement where local distributors could freely experiment with marketing and delivery structures without putting the main franchise at risk. Coca-Cola dispensaries began to spread across the South, selling their drink for five cents a glass (a price that would remain static, for contractual reasons, all the way until 1959).

From $3,000 to Billions

The morphine addiction John Pemberton invented Coca-Cola to cure finally killed him in 1888. Around this point, due to the complicated network of ownership and responsibilities Pemberton left behind when he suddenly died of an overdose, the history of the Coca-Cola brand gets rather murky.

The morphine addiction John Pemberton invented Coca-Cola to cure finally killed him in 1888. Around this point, due to the complicated network of ownership and responsibilities Pemberton left behind when he suddenly died of an overdose, the history of the Coca-Cola brand gets rather murky.

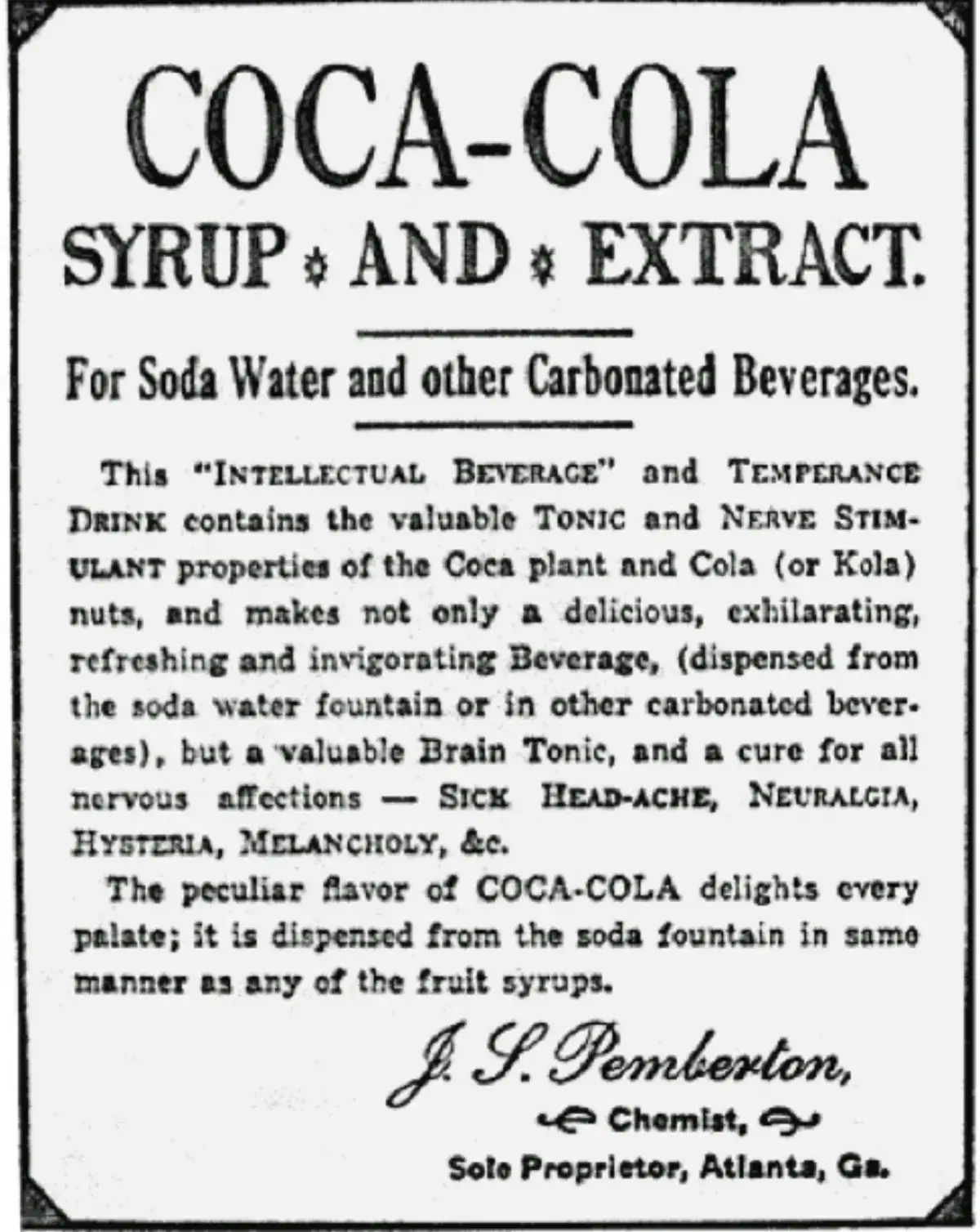

One partner of Pemberton’s, Asa Candler, claimed to have bought a controlling stake in the company before Pemberton died. However, Pemberton’s son, Charley, claimed to hold the rights to the brand name, stating that the recipe was merely being used by Candler under an informal license.

The loose, complex corporate structure that had worked so well for John Pemberton threatened to sink his brand within months of his death if these issues couldn’t be resolved. In the end, Candler solved everything in the most American way he could think of: he threw money at everybody who had a stake in the brand until he was in total control.

By 1891, Candler was Coca-Cola’s sole proprietor, having invested the princely sum of around $3,000 in buying up shares and rights. This was probably for the best, since Candler turned out to be a genius who fundamentally changed the way large businesses operate all over the world.

Coca-Cola History: The Slip of Paper That Changed the World

Even before John Pemberton died, Candler was hard at work building the Coca-Cola brand. In 1885, he may have devised what is now the world-famous Coca-Cola logo, writing out the name in the flowing Spencerian script that every schoolchild had to learn (and which is also the chosen font of the Ford Motor Company and Budweiser, to name two imitators of the approach).

Sources differ on whether it was Candler or Pemberton’s bookkeeper, Frank Mason Robinson, who drafted the design, but Candler evidently thought the world of it and kept it as the official logo for as long as he ran the company.

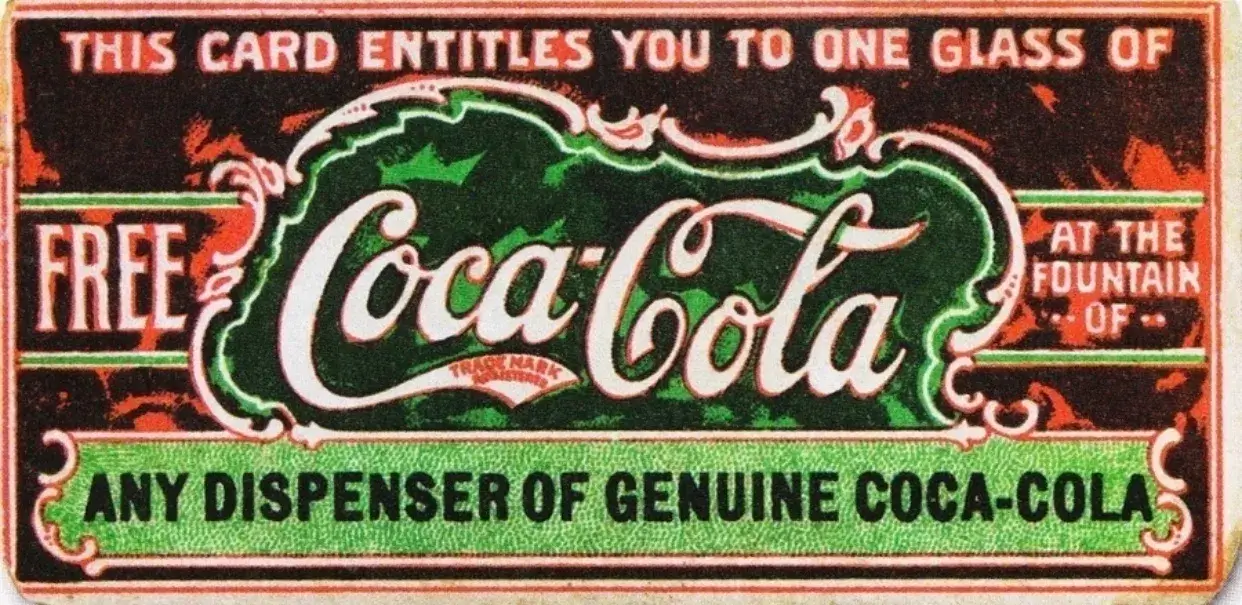

Candler was also tireless in coming up with new ways to share Coca-Cola with the world. In 1886, he started distributing little slips of paper that could be redeemed at the fountain for a single glass of Coca-Cola. While that notion may seem as insignificant as the little slips of paper in question, this seems to be the first instance in history of a company issuing coupons for free samples.

The theory – which proved dead accurate – was that people would be happy to try something new for free, and that they’d be just as happy to pay for it later as loyal customers. Between 1894 and 1913, approximately one in nine Americans drank a free Coca-Cola. With tactics like this, Coca-Cola soon spread across the United States.

Bottling, And the Invention of Santa Claus

Candler was mostly focused on selling Coca-Cola syrup to the pharmacies and fountains that had always been Coca-Cola’s main distributors. The first attempt at actually bottling the product was an informal arrangement with a Vicksburg-based distributor in 1891.

Eight years later, the first Coca-Cola bottling plant was set up in Chattanooga by another independent distributor, who bought the rights to do it for one dollar. The bottling company never did pay Candler that dollar and the loose contract that existed between the two saw them going into and out of court for decades.

Nevertheless, bottled Coca-Cola was a hit, and after the 1898 federal tax on medicines, Coca-Cola stopped marketing itself as a cure-all and left the pharmacy forever. Henceforth, Coca-Cola’s approach to marketing would be positioning itself as a refreshing beverage, one you could drink recreationally — and building up positive emotional associations with the drink among consumers.

It is, of course, a myth that Coca-Cola invented Santa Claus. Many earlier versions of the character had been used to sell mineral water and other products since the 1870s, but it was Coca-Cola that made Santa a jolly fat man in a red suit.

Before that, he had simply been Father Christmas, a lean or tall man in a red, green, or brown suit. Coca-Cola’s appropriation of the image, originally done to boost sales of the cold drink during winter months, created a character that literally billions of children would grow up associating with magic, family, and presents. This paid dividends as those kids grew up and started families of their own.

Perhaps as important as Santa Claus was Coca-Cola’s invention of outdoor advertising. Obviously, ads had existed before Coca-Cola (there’s even a carved advertisement for a local brothel in one ancient Roman city), but Coca-Cola broke the mold for plastering every available surface with its brand.

To this day, Coca-Cola’s brand identity is so powerful that, while blind taste tests actually do reveal most people prefer the taste of Pepsi, non-blind tests, where participants can see the labels, yield the opposite result every time.

Coca-Cola History: Exporting America to the World

In 2012, the Coca-Cola company announced a deal to export its product to Burma. With this venture, Cuba and North Korea were left as the only two countries in the world where you could not legally obtain a bottle of Coca-Cola.

Of course, even in those authoritarian communist dictatorships, the drink is secretly distributed throughout underground black markets alongside other forbidden pleasures such as dirty pictures, cell phones, and PSY’s latest singles.

Just as those black markets exist today, people had been informally exporting Coca-Cola almost from the beginning. Ironically, given the drink’s current status in Cuba, the first rum and Coke seems to have been mixed in a Havana bar in 1900, by a Signal Corps officers who drank a toast to – more irony coming – Cuba’s newly won freedom from Spain.

His cry of “¡Cuba libre!” thus named the drink millions of people would break the ice with at nightclubs over the rest of the century.

Cuba aside, early overseas success for Coca-Cola was limited. Asa Candler’s son and successor, Charley, tried to fire up enthusiasm for the product on a 1900 business trip to England, but Coca-Cola’s total exports to England for that year amounted to five paltry pounds of syrup.

Other efforts to expand into Europe met with similar failure. In Germany, the idea of adults drinking non-alcoholic beverages was absurd — anything other than beer, wine, or water was for children. In France, the very idea that anyone wanted to buy an inferior American beverage was, frankly, insulting.

It fell to a new generation, and another marketing genius, to pry open Europe and establish Coca-Cola as the American standard.

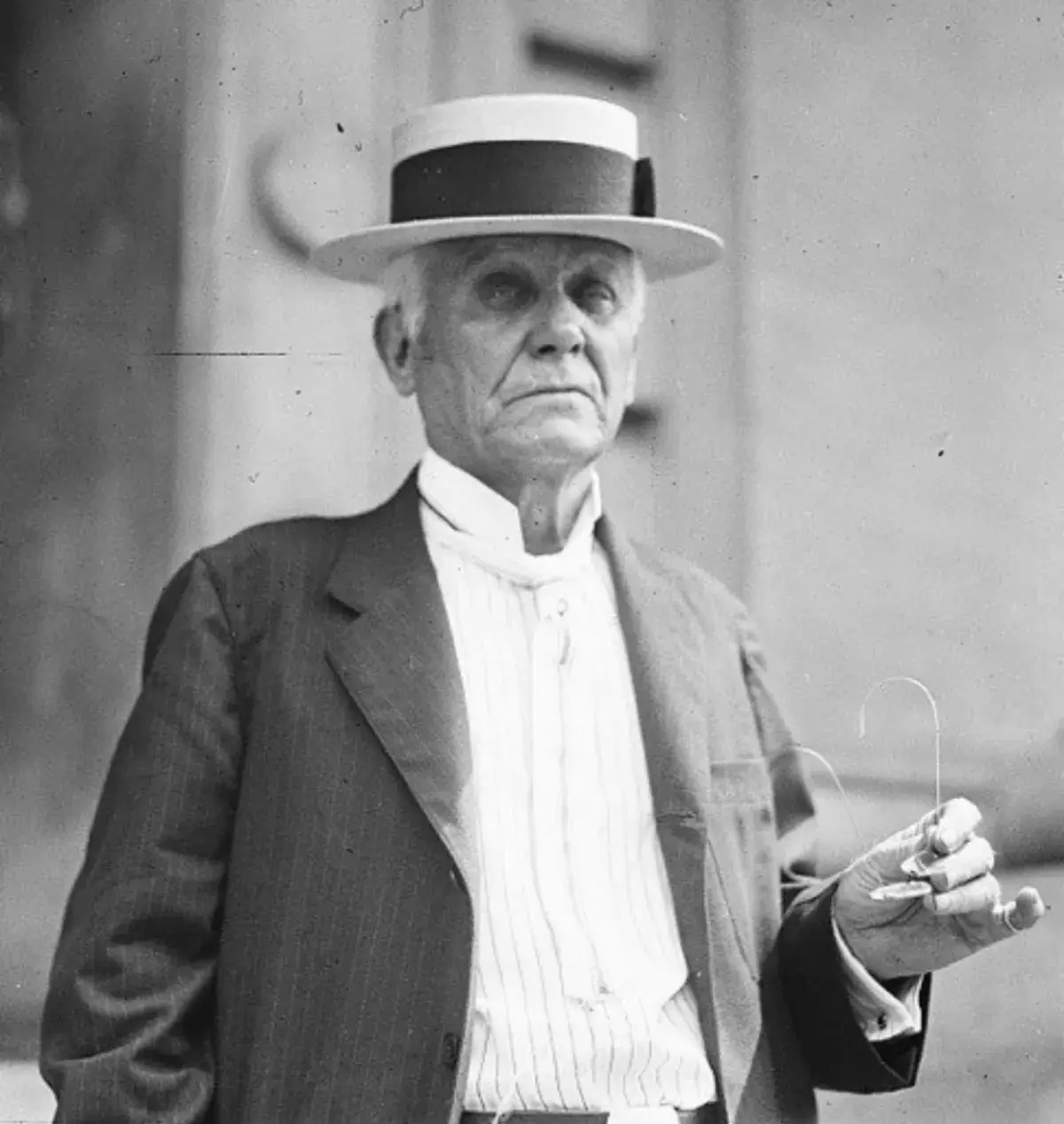

That genius was Ernest Woodruff, who bought the company and took it public in 1919. Woodruff was one of those human dynamos who conquers every inch of the world around him, then chews the scenery until he’s a household name.

Before taking over Coca-Cola’s operations, Woodruff had already risen through the White Motor Company, starting as a truck salesman and finishing as general manager after just a few years. Woodruff then ran Coca-Cola for 60 years, and nothing would ever be the same again.

For starters, Woodruff instinctively realized that bottles were going to be a much bigger seller than fountains overseas. Indeed, it was on his watch that bottled sales passed fountain sales for the first time.

To help make this happen, Woodruff sponsored the development of metal-topped coolers to keep the bottles cold, then invented the six-pack with a handle, so people would buy more Coke to keep those coolers filled. He also pioneered the famous glass-fronted, coin-operated cooler that dispensed a single bottle for a nickel, and which would be a fixture of every single gas station in America for half a century.

Eventually, Woodruff turned his dynamic energy toward overseas markets, resolving that there wouldn’t be one place on Earth that didn’t have a Coca-Cola handy.

Coca-Cola’s first organized attempt to market overseas started in 1926 when the company opened an office devoted to buying the world a Coke. Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, Coca-Cola was advertised, given away, and sold all over Europe as a fun, refreshing import from exotic America.

The company even developed a special “export bottle” for foreign consumers. These bottles were dark green and closely modelled on champagne magnums, presumably on the theory that the French would be more likely to drink it if it looked like wine. The export bottle even had a gold-foil seal over the cap.

If you happen to find one of these in your grandparents’ attic, be sure to let somebody know; on the rare occasion they come up at auction, authentic export bottles command thousands of dollars each. Even the official Coca-Cola museum only has three surviving bottles from this early attempt at global expansion.

The Triumph of Democracy

Woodruff had an instinctive grasp of what made a successful marketing campaign. In 1928, the U.S. Olympic team arrived in Amsterdam with 40,000 bottles of Coca-Cola, its official sponsor.

The association of Coca-Cola products with the Olympics continues to this day, and probably played a role in the Olympic committee’s choice to host the 1996 Centenary Games in Atlanta, the site of Coca-Cola’s corporate headquarters.

Woodruff also forged links between Coca-Cola and the U.S. military. At the outbreak of World War II, he swore that American servicemen would be able to get a cold Coca-Cola everywhere the war took them. With very few exceptions, he was as good as his word.

Soldiers all over the European Theatre had bottles of Coca-Cola waiting for them in rear areas almost before they had replacement socks and gloves, and the drink followed soldiers to Japan during the post-war occupation.

Naturally, with every soldier swigging Coca-Cola from the bottle practically every time a unit stopped for rest, people in the liberated countries came to associate the drink with the American soldiers, who were generally willing to share.

Overnight, Coca-Cola, along with Hershey’s chocolate and Spam, became an American hallmark. Eventually, the American forces withdrew from occupation duty, but the products they had introduced to a generation of foreigners remained behind.

Global Dominance

Today, Coca-Cola is sold virtually everywhere in the world. Researchers working at the South Pole can enjoy a frosty Coca-Cola in the sub-zero temperatures. Mountain climbers in the high Himalayas can stop for a Coca-Cola at their basecamp 20,000 feet above sea level – so high that breathable air itself is a rare commodity.

The drink was even carried into space – on the July 12, 1985, anniversary of the billionth bottle – aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger for very important research into whether water can be carbonated in microgravity (it can).

Every day, people all over the world drink 1.9 billion servings of Coca-Cola between them. It is, by some measures, the most widely distributed product in history. The brand’s humble, up-by-the-bootstraps origin story, its history of innovation in both marketing and technology, and its close association with American men in uniform have made Coca-Cola virtually synonymous with America’s image overseas.

This close association has mostly worked for the company, but sometimes it gets in the way. Just before World War II, for example, no less than leading Nazi Hermann Göring blocked the import of Coca-Cola syrup into Germany unless a huge bribe was paid. The company then created Fanta as a way to enter the German market.

Other countries, as they’ve passed through their own anti-American periods, have also vented their rage at Coca-Cola. As of now, however, the official word from Islamic authorities is that Coca-Cola is halal since the Quran doesn’t explicitly forbid drinking it.

That this question even came up, or that there really is a competing product called Mecca-Cola, shows what a double-edged sword Coca-Cola’s 130-year-old marketing strategy has been. Either way, the product has been linked with America in the world’s consciousness, for better or worse, and it’s unlikely to change anytime soon.

* * *