By: Robby Berman | Guest Writer

Key Takeaways

- A study analyses data from the Kepler Space Telescope and the European Space Agency’s GAIA survey to estimate the number of habitable planets.

- There may be 30 such planets in our own galactic neighbourhood.

- The new estimate may help inform future research and missions.

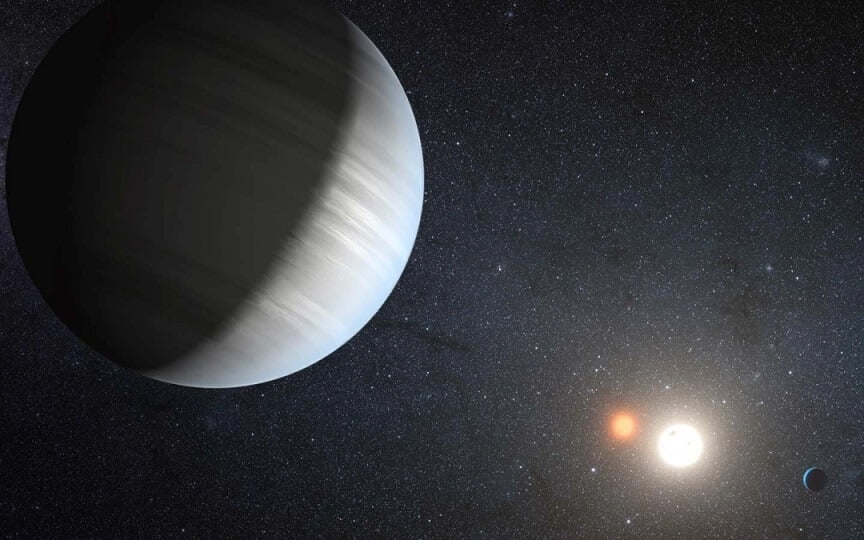

Throughout its nine-year tour of duty that concluded in 2018, NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope produced a massive amount of observational data. Scientists are still going through it all. Among its revelations were now-confirmed 2,800 exoplanets, with thousands more still being analysed. A new study of its data suggests that there may be as many as 300 million inhabitable planets in our galaxy. It finds that several of these could be relatively close by, within 30 light years from here.

Co-author Jeff Coughlin stated in a SETI press release that “this is the first time that all of the pieces have been put together to provide a reliable measurement of the number of potentially habitable planets in the galaxy.”

(We previously wrote about a specially designed calculator that determined there could be exactly 36 contactable civilizations.)

The research, a collaboration between NASA, SETI, and other organizations, will be published in The Astronomical Journal — you can see the pre-press version at arxiv.org.

The team that produced the new report was led by Steve Bryson of NASA’s Ames Research Centre in California. The authors of the study looked for stars that are similar in size, age, and temperature to our Sun, between 4,527 to 6,027 °C. These stars are either G dwarfs, or slightly smaller and more plentiful K dwarfs. Next, they looked for planets orbiting such stars that ranged in size from 0.5 to 1.5 times the size of Earth on the assumption that they were most likely to be rocky planets like ours.

A big factor affecting habitability is the ability to support surface water. Earlier estimates of habitable planets have focused primarily on an exoplanet’s distance from its sun, the so-called “habitable zone.” The new research also takes into consideration the amount of light the planet receives from its sun as a factor in the likelihood of water. The authors of the study supplemented the Kepler data with spectroscopic measurements from the European Space Agency’s GAIA survey of a billion stars in the Milky Way.

The stars can be dim enough that their habitable zones are close, causing any exoplanets there to be tidally locked, which means the same side always faces their sun. This makes the stripping off of their atmospheres more likely. One of the unknowns is the degree to which a planet’s atmosphere impacts its ability to retain water, though, and for the current research, the authors presumed that atmosphere has a minimal effect on the likelihood of surface water.

Taking all this into consideration, the research “estimate with 95% confidence that, on average, the nearest HZ planet around G and K dwarfs is ∼6 pc away, and there are ∼ 4 HZ rocky planets around G and K dwarfs within 10 pc of the Sun.” (pc is the abbreviation for parsec.)

The study offers both a conservative estimate of the number of habitable exoplanets orbiting their stars — 0.37 to 0.60 planets per star — and a more optimistic one: 0.58 to 0.88 per star. More than half of galaxy’s suitable stars may have habitable planets.

On a basic level, Coughlin notes, the study means “we’re one step closer on the long road to finding out if we’re alone in the cosmos.”

The research may also prove useful in targeting future study and missions. Says Michelle Kunimoto of the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite group at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, “Knowing how common different kinds of planets are is extremely valuable for the design of upcoming exoplanet-finding missions.” She adds that “surveys aimed at small, potentially habitable planets around Sun-like stars will depend on results like these to maximize their chance of success.”

* * *

NEXT UP!

Scientists Find Out If A Lashing Dinosaur Tail Could Generate A Sonic Boom

Every once in a while, scientists embark on a study to test some weird and wacky hypothesis that makes you wonder why. But let’s indulge them; it can be fun

A new study from a team of palaeontologists and aerospace engineers has simulated a dinosaur‘s tail as it lashes about, all to see whether long-necked sauropods could whip their appendages faster than the speed of sound – quick enough to produce the crack of a small, supersonic boom.

Previous research has suggested the dinos could, if their tails had a bullwhip-like structure adding length. If that were true, these herbivorous dinosaurs might have used their tails to defend themselves against predators or nosy neighbours.

* * *

READ MORE: A Dinosaur Killed On The Day of The Fatal Asteroid May Have Been Discovered

Interesting: Scientists Collect First RNA From An Extinct Tasmanian Tiger

Liked it? Take a second to support Collective Spark.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Collective Spark Story please let us know below in the comment section.