By: Dave Roos | How Stuff Works

It was supposed to be the largest single repository of classical knowledge in the ancient world, the holder of all the “books” known at the time. Built by the Greek-speaking Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt in the third century B.CE., the Library of Alexandria was said to contain hundreds of thousands of papyrus scrolls (as many as 700,000 according to one ancient source) as part of one king’s Herculean effort to collect “all the books in the world.”

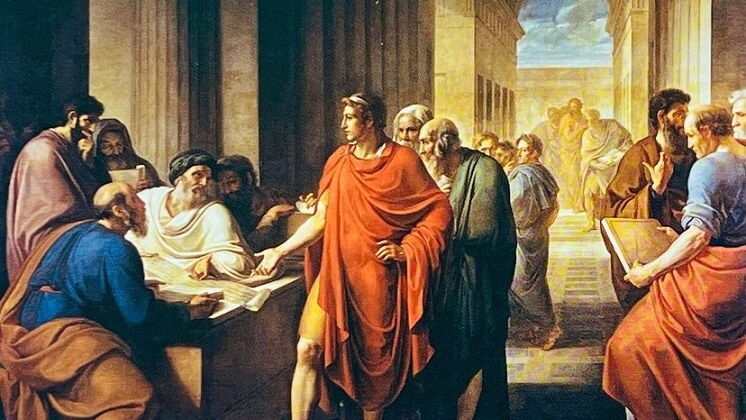

Great minds of the Hellenistic period studied and taught in Alexandria, a cosmopolitan capital on the Mediterranean founded by Alexander the Great. The mathematician and geographer Eratosthenes lived there, as did Aristarchus, the first astronomer to argue that the planets orbited the sun. They and others were referred to as the “heads” of the Alexandrian Library by various ancient authors, and we can easily picture these beard-and-toga geniuses hunched over scrolls inside a magnificent, colonnaded hall.

And then comes the tragic part: Julius Caesar started a fire to destroy the library and that — along with the later fall of the Roman Empire — is to blame for the collective loss of knowledge that plunged Western civilization into the Dark Ages.

But is this true?

As intellectually vibrant as Alexandria was and as large as the Library of Alexandria looms in our imagination, “our actual information about that period, and specifically for the library, is pretty thin,” says Thomas Hendrickson, an historian of ancient libraries and their legacies. “If the Library of Alexandria really existed, we don’t have any information about it. But even the legend of the library seems to have been a huge inspiration for the entire ancient world.”

The Legend Begins With A Fake Letter

In the third century B.C.E., right when the Library of Alexandria was amassing its record-breaking archive of scrolls, a man named Aristeas wrote a letter to his brother Philocrates. Aristeas claimed to be a courier to the ruling king in Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus. In his letter, Aristeas gave a first-hand account of how the Library of Alexandria came to be, and how very big it was:

“Demetrius of Phalerum, the president of the king’s library, received vast sums of money for the purpose of collecting together, as far as he possibly could, all the books in the world. … On one occasion when I was present he was asked, ‘How many thousand books are there in the library?’ and he replied, ‘More than two hundred thousand, O king, and I shall make endeavours in the immediate future to gather together the remainder also, so that the total of five hundred thousand may be reached.”

The “Letter of Aristeas,” as it’s known, provides the earliest description of the monumental Library at Alexandria, and portrays it as a truly “universal” library intent on collecting and translating into Greek all of the knowledge of the ancient world.

“The problem with the ‘Letter of Aristeas’ is that it’s a total forgery,” says Hendrickson, who teaches at the Stanford University Online High School.

Most scholars date the letter to a century later (second century B.C.E.) and doubt the very existence of Aristeas. The forged letter is usually described as Jewish “propaganda” intended to show the importance of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (known as the Pentateuch). The letter’s author was trying to magnify the size and importance of the library and claim that Ptolemy II himself had insisted that the Hebrew Bible be included in this repository of all great knowledge.

Other ‘Facts‘ About The Library

But even some non-fake ancient writers chimed in about how many volumes were really held at the Alexandrian Library, and those estimates vary wildly.

Seneca, the Roman philosopher, wrote in 49 C.E. that “forty thousand books were burnt at Alexandria,” in reference to Caesar’s alleged destruction of the library. Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman historian writing three centuries later, claimed that 700,000 scrolls, “brought together by the unremitting energy of the Ptolemaic kings,” were destroyed during the Alexandrian war.

The Roman physician Galen, writing in the second century C.E., said that Ptolemy II was able to amass such a huge collection because he forced all incoming merchant ships to hand over any books on board. The king’s scribes would then make copies of the books, deliver the copies to the owners and keep the originals for the library.

The historian Roger Bagnall called the six-figure estimates “outlandish” and calculated that if every single known Greek author of the third century B.C.E. produced 50 scrolls each that would still have resulted in only 31,250 volumes. To arrive at figures like 200,000 or 700,000 scrolls presumes that historians are unaware of 90 percent of ancient Greek writers or that hundreds of identical copies of each text were kept in the library.

The Romans Ran With The Idea

While the actual number of scrolls in the Alexandrian Library is fuzzy at best, one thing is clear: “This legendary notion of a library as a ‘universal library’ did inspire real libraries,” says Hendrickson.

Julius Caesar returned from the Alexandrian war with big plans for building a library that would rival the Ptolemies in Egypt, but he was assassinated before it could come to fruition. Caesar Augustus took up the task and built a large library on the Palatine Hill. Later Roman leaders built their own libraries, but Hendrickson says that we don’t know how exactly those libraries functioned in a largely illiterate society.

“Ancient books were extremely valuable since each one was handmade, so it’s unlikely that the Romans were loaning these out to people on the street,” says Hendrickson. “It’s possible that Roman libraries were more like museums, these big monumental spaces where people could walk through and see statues of the poets and these impressive books.”

In fact, the very first museum or Mouseion, as it was known, was also in Alexandria. Its ancient function is also hotly debated by historians and academics, but its name — which means “seat of the Muses” — implies that it was a place of research and creative output.

The famed Library of Alexandria may have actually been inside the museum, according to Strabo, a Greek philosopher and historian who lived at the turn of the millennium. When talking about Alexandria’s great collection of books under Ptolemy II, Strabo refers to the museum library and a smaller library called the Serapeum, but never mentions the “great” Library of Alexandria as a separate structure. So far, archaeologists have not found any remains that definitively point to this library either.

Was The Library Destroyed?

“You will never find a library that’s been destroyed more times than the Library of Alexandria,” says Hendrickson. That’s because ancient writers loved to accuse their enemies of being barbaric fools who would burn down a fortress of knowledge.

As mentioned, Julius Caesar usually gets the blame and that’s because Caesar himself claimed to have burned his way out of Alexandria in his war against rival Pompey in 48 B.C.E. Caesar ordered his troops to set fire to Pompey’s ships in the Alexandria harbour, and the conflagration spread to nearby warehouses and allegedly to the library.

But Caesar isn’t the only suspect. Later Roman emperors also sacked Alexandria in their military campaigns, and in 391 a group of Christian monks were reported to have destroyed the Serapeum, the “daughter” library to the legendary Library of Alexandria. Could it have been anti-pagan Christians who robbed the ancient world of this repository of classical knowledge? We’ll never know. (In the seventh century C.E., Christians blamed the Muslim Caliph Amr for burning Alexandria’s books.)

While these ancient accusations of book burning were effective smear campaigns, there’s no reason to believe that the Library of Alexandria was, in fact, destroyed. It could have simply fallen into disrepair, wrote the historian Bagnall.

Papyrus scrolls were extremely fragile — not a single ancient scroll survives from the humid Mediterranean region, unlike those from the drier climate of Egypt. To keep the library going, scribes would have had to continuously make fresh copies of each scroll every few years, a truly Sisyphean task. If the Ptolemies or later rulers of Alexandria didn’t invest heavily in the library’s upkeep, its scrolls would have rotted away.

“It is not that the disappearance of a library led to a dark age, nor that its survival would have improved those ages,” wrote Bagnall. “Rather, the dark ages, if that is what they were, … show their darkness by the fact that the authorities both east and west lacked the will and means to maintain a great library.”

The Library of Alexandria’s Legacy

What’s far more interesting to library historians like Hendrickson and Bagnall than how many books the library held or how it was destroyed is how the very idea of a “universal” library in Alexandria — legendary or not — inspired the creation of ambitious libraries in the Renaissance and into the modern era.

“Every one of our great contemporary libraries owes something to [the Library of Alexandria],” continued Bagnall.

Without this ancient image, we might not have something like the Library of Congress, the closest thing to a “universal” library on the planet. The Library of Congress holds 51 million catalogued books and 173 million total items including rare books, maps, sheet music and sound recordings.

Now That’s Cool

Nearly 2,000 ancient papyrus scrolls were recovered from the ruins of a city destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79, but the carbonized scrolls proved impossible to read. Now a team of scientists is using high-resolution X-ray technology to try to decipher what could be the oldest papyri on the planet.

* * *

READ MORE: Ancient Hall of Records Found In Romania Kept Secret Since 2003

Read more on Ancient Library’s: The Library of Ashurbanipal: The Oldest Known Library That Inspired the Library of Alexandria

Liked it? Take a second to support Collective Spark.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Collective Spark Story please let us know below in the comment section.