By Caleb Strom | Ancient Origins

The tomb of the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, despite being involved in one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of all times, endures as a mystery to archaeologists and historians as it remains largely sealed up and unexplored. The strange and deadly history of the tomb and its contents was sealed within and buried beneath vegetation for thousands of years.

The two decades following 218 BC was a period of instability in the Mediterranean as the Roman Republic went to war with the Carthaginians. In the Far East, by contrast, this period was relatively stable, as a unified China emerged from the chaos of the Warring States Period. Qin Shi Huang was the man responsible for uniting the seven warring states to form the first imperial dynasty of China. The first emperor of China was as obsessed with life as he was with the afterlife. Whilst occupied with the search for the elixir of immortality, Qin Shi Huang was also busy building his tomb.

A 2017 study of ancient texts written on thousands of wooden slats reveals the extent of the emperor’s power and his desire to live forever. The artefact includes an executive order from Emperor Qin Shi Huang for a nationwide hunt for the elixir of life and also the replies from local governments. One village, called “Duxiang“, reported that no miraculous potion had been found there yet but assured the emperor that they would continue to search. Another place, “Langya,” claimed to have found an herb on an “auspicious local mountain,” which could do the job.

As a matter of fact, the construction of the emperor’s tomb began long before Qin Shi Huang became the first Chinese emperor. When Qin Shi Huang was 13 years old, he ascended the throne of Qin, and immediately began building his eternal resting place. It was only in 221 BC, however, when Qin Shi Huang successfully unified China that full-scale construction would begin, as he then commanded manpower totalling 700,000 from across the country. The tomb, located in Lintong County, Shaanxi Province, took over 38 years to complete, and was only finished several years after his death.

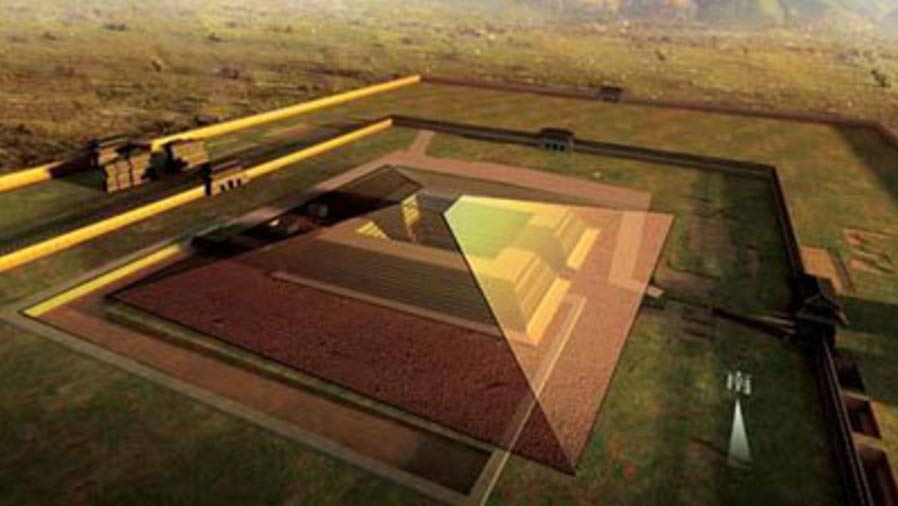

An account of the construction of Qin Shi Huang’s tomb and its description can be found in the Records of the Grand Historian, which was written by the Han dynasty historian, Sima Qian. According to this source, Qin Shi Huang’s tomb contained ‘palaces and scenic towers for a hundred officials’, as well as numerous rare artefacts and treasures. In addition, the two major rivers of China, the Yangtze and the Yellow River, were simulated in the tomb using mercury. The rivers were also set mechanically to flow into the great sea. Whilst the rivers and other features of the land were represented on the floor of the tomb, its ceiling was decorated with the heavenly constellations. Thus, Qin Shi Huang could continue to rule over his empire even in the afterlife. To protect the tomb, the emperor’s craftsmen were instructed to make traps which would fire arrows at anyone who entered the tomb.

Qin Shi Huang’s funeral was conducted by his son, who ordered the death of any concubines of the late emperor who did not have sons. This was done in order to provide company for Qin Shi Huang in the afterlife. When the funerary ceremonies were over, the inner passageway was blocked, and the outer gate was lowered, so as to trap all the craftsmen in the tomb. This was to ensure that the workings of the mechanical traps and the knowledge of the tomb’s treasures would not be divulged. Finally, plants and vegetation were planted on the tomb so it resembled a hill.

Although a written record regarding Qin Shi Huang’s tomb was already in existence roughly a century after the emperor’s death, it was only re-discovered in the 20th century (whether the tomb has been robbed in the past, however, is unknown). In 1974, a group of farmers digging wells in Lintong County dug up a life-size terracotta warrior from the ground. This was the beginning of one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of all times. Over the last four decades, about 2000 terracotta warriors have been uncovered. It is estimated, however, that a total of between 6000 and 8000 of these warriors were buried with Qin Shi Huang. Furthermore, the terracotta army is but the tip of the iceberg, as the emperor’s tomb itself remains unexcavated.

It is unlikely that the tomb of Qin Shi Huang will be opened any time soon. For a start, there are the tomb’s booby traps, as mentioned by Sima Qian. Despite being over two millennia old, it has been argued that they would still function as effectively as the day they were installed. Furthermore, the presence of mercury would be incredibly deadly to anyone who entered the tomb without appropriate protection. Most importantly, however, is the fact that our technology at present would not be adequate to deal with the sheer scale of the underground complex and the preservation of the excavated artefacts. As a case in point, the terracotta warriors were once brightly painted, though exposure to the air and sunlight caused the paint to flake off almost immediately. Until further technological advancements have been made, it is unlikely that archaeologists will risk opening the tomb of the first emperor of China.

This article (The Secret Tomb of The First Chinese Emperor Remains An Unopened Treasure) was originally published on Ancient Origins and is published under a Creative Commons license.