By: Bipin Dimri | Historic Mysteries

Ancient Egypt, for much of its history, relied on the protection of the vast deserts that surrounded it to the west and the south. Huge and inhospitable, few would dare to cross them in anger and face the might of the Egyptian army.

To the east, with the Sinai peninsula, the Egyptians faced frequent aggressive incursions from their neighbors in the levant. However, despite the formidable protection of the deserts, the Egyptians faced another overland threat.

The Nile, source of all life for the Egyptians, extended far to the south of the Egyptian heartlands, and here Egypt faced their only other major land neighbour. This region, known as Nubia, would at times by subjugated by the Egyptians, and at other times rule the Egyptian kingdoms as Pharaohs of the South.

One of the civilizations that rose from the south to threaten Egypt was the Kingdom of Kush. And it was the Kushites, fleeing an ascendant Egypt in the 6th century BC, who built a great city far to the south: Meroe, known to the Greeks as Aethiopia.

It’s Safer in The South

This ancient city was found on the Nile’s west bank in Sudan. The Kushites had threatened Egypt’s southern border for 200 years, striking from their capital of Napata.

But in 591 BC the Egyptians scored a stunning victory against Kush, and Pharaoh Psamtik II had sacked Napata. The Kushite remnants under King Aspelta, retreating from Egyptian dominance, relocated their capital far the south.

The choice of Meroe as the new capital was wise. Rich resources and fertile lands ensured that the new centre of power flourished, and the Kushites re-established themselves in splendour. Trade routes ranging as far as India and even China brought wealth to the kingdom, and over 200 pyramids would eventually be built at Meroe.

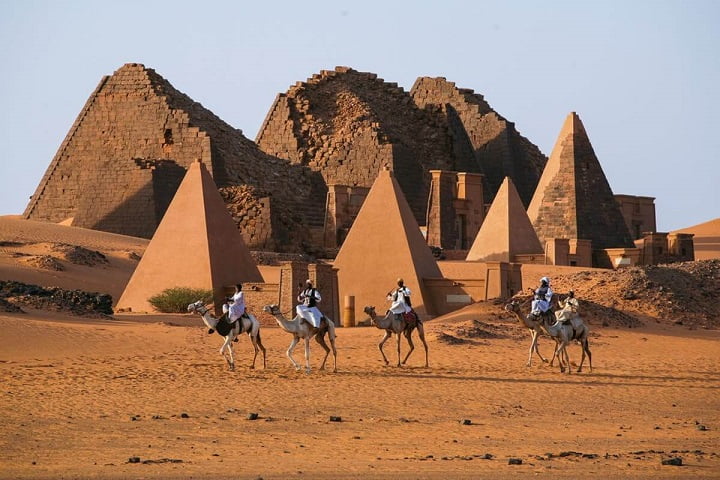

Many of these pyramids today are in ruins, but what remains shows the distinctive proportions and sizes of Nubian pyramids. Slender and with steeper walls, and often with grand entrances, they appear very different to Egyptian pyramids.

The pyramids at Meroe range from 20 feet to 100 feet (6 to 30 m) tall. They were believed to have been built between 720 BC and 300 BC. The entrance of the pyramids usually faces towards the east to greet the rising sun.

Moreover, the pyramids have decorative elements inspired by the great cultures to the north: Rome, Greece, and Egypt. This mingling of sources with Kushite architecture makes the pyramids unique.

According to the National Museum of Sudan’s head, Abdel-Rahman Omar, many of the pyramids retained their golden capstones as late as the 19th century. However, a number of overeager archaeologists, little more than looters, removed these priceless features and even reduced some of the pyramids to mere rubble.

Today the remaining pyramids at the city of Meroe are largely forgotten, and the site lies deserted. Even though it is a UNESCO World Heritage site, it is rarely visited.

The Discovery of Meroe

Records had survived from the classical period of this great city, somewhere far to the south of ancient Egypt. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, described the city of Meroe and its queens, called Candaces.

These queens are also mentioned in the Bible, and Jewish oral tradition claims that Moses at some point, while still a favourite of the Egyptian Pharaoh, led an army into Nubia and besieged Meroe, here called Saba. After taking the city through betrayal, he returned north victorious.

These ancient reports of a fabulous city somewhere in the sands cast a spell on the scholars of the 19th century. A French archaeologist named Frederic Cailliaud was desperate to prove the city’s existence.

During that time, Khedive Ismail, ruler of Egypt and Sudan, was ambitious to acquire all the riches of Sudan. So, Frederic Cailliaud attempted to interest Ismail to join him in the search for the city of Meroe.

However, the prince had little interest in history and science and did not show much interest. Seeking to entice the Khedive, Frederic Cailliaud gave Ismail a hint that he was trying to discover King Solomon’s gold mine.

Supported by the newly enthusiastic Ismail, Frederic Cailliaud conducted extensive exploratory journeys into Sudan. After much searching, on the dawn of 25th April 1821 he walked into the ruined city of Meroe, confirming its existence and location for all time. He was so overwhelmed with emotions that made him sit down and weep.

The Heart of an Empire

Meroe was the centre of a flourishing kingdom. Abundant iron ore reserves located nearby and its location as a gateway to southern Africa ensured the city was a powerful and wealthy trade hub.

Evidence of ancient blast furnaces at the site show the prominence and importance of metalworking to the Kushites. Iron was an extremely valuable resource and the production was controlled in a centralized manner within the Meroe empire.

This concentration of experience and talent meant that the Meroitic metalworkers were considered the best in the world. The city of Meroe was also involved in exporting jewellery and textiles. The textiles were mainly based on cotton.

Pottery was also a key trade good for the Kushites and production was quite widespread. One of the strong traditions was the production of decorated, fine pottery jars and bowls, used for mortuary rites.

The key to the political and social success of Meroe, and the Meroitic empire that flourished around it, was the availability of labour to exploit the resources. This access to labour drove the wealth of the region and in turn led to the rise of political power in Meroe. Aspelta was canny indeed to have chosen Meroe as his capital.

This focus of power and wealth led to engineering advancements, and Meroe was able to exploit the Nile like no southern kingdom had before. The “sakia”, a mechanical water-lifting device, moved water for irrigation and crop production, opening up large areas of barren land for agriculture and allowing the population of the city to grow.

The Meroese also had their own spin on religion. The people living in Meroe had several southern deities like the lion-son of Sekhmet and Apedemak. However, the gods of Egypt cast a long shadow and deities were Horus, Thoth, and Isis were also worshipped, a throwback to the days when the capital was much closer to Egypt.

The Fall of Meroe

By the late 1st century BC, Egypt had been conquered by the Roman empire and Meroe faced a new adversary. The Romans responded to the Kushite raids into Egypt in force, marching south and again sacking the old capital of Napata.

The Meroese made peace with the Romans, adapting to the new political climate and maintaining their position as a trade hub. However, over the next three centuries, as power shifted away from their neighbour Egypt, Meroe went into decline.

This diminishing of power coincided with the rise of new powers in the region. One such was Axum, an upstart kingdom and rival trading hub to the east, centred in modern-day Ethiopia. Meroe’s prestige as a trade hub had been declining and Axum took advantage, growing in wealth and power.

An expansionist culture with an effective military, Meroe was one of the targets of the Axum as they sought dominance in the region. In 350 AD, after more than 900 years as the Kushite capital, The armies of the Axum destroyed Meroe, leaving a stele behind to record their victory. Meroe was no more.

Archaeology

It took a long time for the secrets of Meroe to be uncovered. Their unique language, their two writing systems, and the treasures of the city itself remained almost entirely a mystery to western archaeology before Cailliaud rediscovered the city in 1821.

In 1944, C. R. Lepsius again excavated the ruins. In addition to discovering further antiquities, he also conducted extensive surveys of the site, completing many sketches and plans.

Further excavations were conducted in 1902 and 1905. Remains of bodies, earthenware, metal vessels, and ruins of temples and palaces were discovered.

But, driven out of reach of most by the modern-day turmoil that grips Sudan, the ruins of Meroe remain inaccessible to many. Much of what the city was is now known, but much remains a mystery. What hidden treasures lie hidden in this ancient, forgotten city of Kush, waiting to be discovered?

* * *

NEXT UP!

Drought Reveals 113-Million-Year-Old Dinosaur Tracks In Texas

Drought has dried up part of a river in central Texas, revealing 113-million-year-old dinosaur tracks.

The prehistoric footprints emerged at Dinosaur Valley State Park, which is located in the town of Glen Rose, southwest of the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

As the name suggests, the park already protects other dinosaur footprints. But the tracks that recently emerged are usually hidden under the mud, silt and waters of the Paluxy River. This summer, however, water levels have dipped so low that the prehistoric indentations are now visible. So far, volunteers have counted 75 newly exposed footprints in the parched riverbed.

* * *

READ MORE: This Ancient Maya City Was Hidden In The Jungle For More Than 1,000 Years

And more Archaeology News: Guanches: Ancient Mummies of The Canary Islands (Video)

Liked it? Take a second to support Collective Spark.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Collective Spark Story please let us know below in the comment section.