DNA From 2,000-Year-Old Skeletons Hints At The Origins of Syphilis

In contrast to a common theory, new findings suggest Columbus-led expeditions may not have transported syphilis to Europe from the Americas, though they cannot disprove the claim with certainty.

By: Christian Thorsberg | Smithsonian

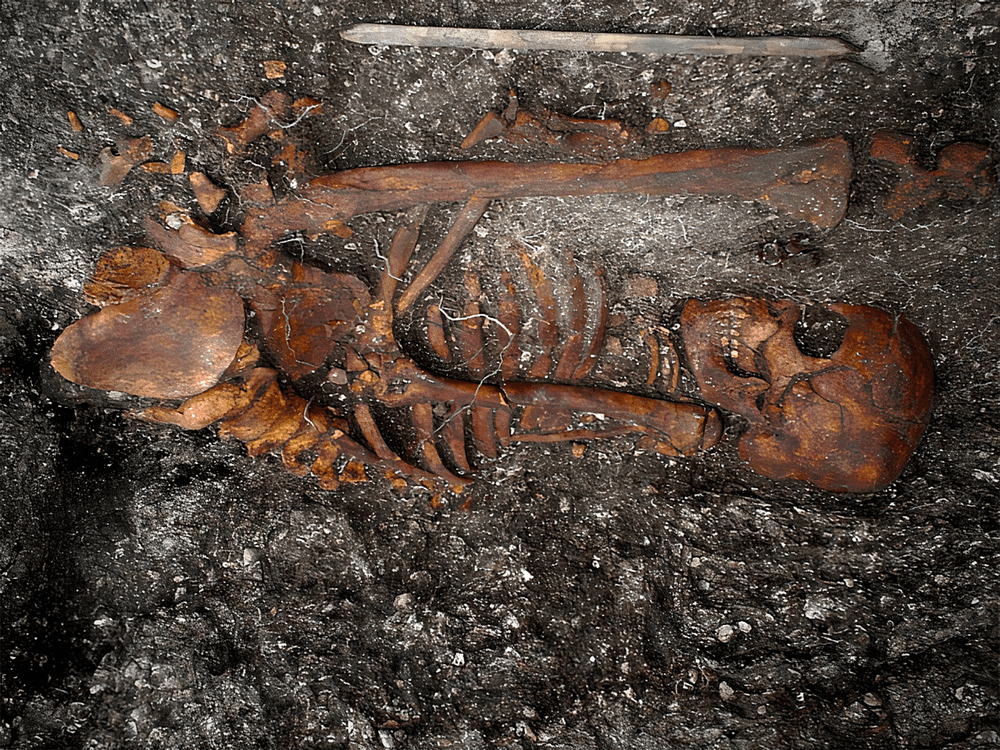

Two-thousand-year-old human remains uncovered from a burial site on the south-eastern coast of Brazil have offered scientists insight into the surprisingly ancient origins of syphilis and its related illnesses.

Syphilis is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, and other related bacteria lead to similar conditions such as bejel and yaws. The origin of these diseases, known as treponemal infections, has been a source of speculation for historians for centuries—with syphilis, which is sexually transmitted, drawing particular interest.

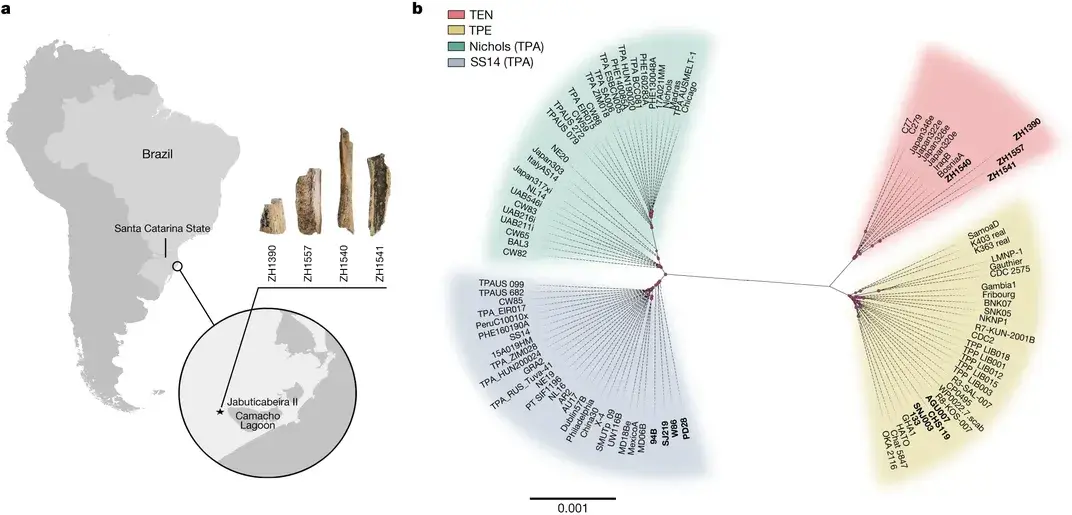

Despite warm and moist conditions at the burial site, known as Jabuticabeira II, researchers discovered well-preserved, though incomplete, skeletons. These contained physical evidence of ancient treponemal infections, including bone lesions and inflammation. The team also took DNA samples from four individuals, which provided genomic evidence of an ancient T. pallidum bacteria strain most similar to modern-day bejel, a non-sexually transmitted disease prevalent in the hot and dry eastern Mediterranean and Saharan West African regions.

The findings, which suggest T. pallidum was more widespread and much older than thought, were published last week in the journal Nature.

“This study is incredibly exciting, because it is the first truly ancient treponemal DNA that has been recovered from archaeological human remains that are more than a few hundred years old,” Brenda J. Baker, an anthropologist at Arizona State University who wasn’t involved with the study, tells CNN’s Katie Hunt.

Additionally, the new study provides another clue about the origin of syphilis—and it adds credence to a growing library of research that disputes a prominent theory. Earlier researchers had suggested that people returning from Christopher Columbus-led expeditions to the Americas brought back syphilis—introducing it to Europe in the 15th century and kick-starting the epidemic that killed up to five million people across the continent.

“It is very clear that Europeans took a number of diseases [including smallpox] to the New World, decimating the native populations, so the hypothesis that the New World ‘gave syphilis to Europe’ was attractive to some,” Sheila A. Lukehart, an infectious disease and global health expert at the University of Washington who didn’t take part in the study, tells CNN.

The study, however, seems to erode this theory. “Of course, we cannot prove it wrong,” senior author Verena Schünemann, a paleogeneticist at the University of Zurich, tells Business Insider’s Marianne Guenot. “But it seems that there’s a much more complex story developing than these hypotheses are capturing currently.”

Notably, the bacterium strain found by the researchers was not a type that is sexually transmitted, so it “leaves the origin of the sexually transmitted syphilis still unsettled,” says lead author Kerttu Majander, an archaeologist at the University of Basel in Switzerland, in a statement.

Earlier discoveries have suggested T. pallidum originated in Eurasia or Africa and was introduced to the Americas by some of the continents’ first inhabitants, and others have concluded that treponemal diseases were widespread in Europe well before Columbus crossed the ocean.

Skeletons With Rings Around Their Necks Uncovered At A 1,000-Year-Old Cemetery In Ukraine

“All this points in the direction that they are not being imported from the Americas,” Schünemann tells Nature News’ Ewen Callaway.

The work also suggests the treponemal timeline is more complex than thought. The ancient T. pallidum samples were notably dissimilar from modern-day yaws and syphilis strains—both of which are more prevalent in South America today—indicating that current treponemal diseases have evolved distinct lineages within the past few millennia.

Further, genetic analysis of the ancient bejel strains revealed that at the time of the deaths in Brazil, T. pallidum lineages had already been progressing and possibly infecting humans for 12,000 years—about 10,000 years longer than scientists had previously thought, per Nature News.

While syphilis samples were not directly found in the bones, the ancient evidence of T. pallidum is still a crucial indicator for uncovering the history of the devastating disease, which has affected millions of people across the world and remains prevalent today. At the very least, the team affirms that treponemal diseases existed in the Americas before Europeans arrived, per the statement.

The researchers hope their discovery will lead to greater revelations—and possibly a definitive answer—on the prehistoric origins of the sexually transmitted disease. Other scientists note that technological innovations will help the effort in the future.

“The search for the origin of syphilis is really a search for the origin of the Treponema [bacteria],” Lukehart tells Nature News. To CNN, she adds: “The modern tools available for extracting DNA from ancient samples, for enriching the treponemal DNA, and obtaining deep sequencing from samples has rapidly increased our understanding of the Treponema.”

* * *

NEXT UP!

700,000-Year-Old Skull Found In Greece Completely Shatters ‘Out of Africa Theory’

In 1959, a human skull, that has been dated back 700,000 years and is now known as the “Petralona Man” or the “Archanthropus of Petralona,” was unearthed. Since that time, researchers have been pondering the question of where exactly this skull came from, which has sparked a significant amount of discussion.

The skull, which was found lodged in the wall of a cave in Petralona, located close to Chalkidiki in Northern Greece, is considered to be the oldest human “Europeoid” (showing European traits). A shepherd accidentally discovered the cave, which was filled with stalactites and stalagmites. In the following years, researchers also unearthed a vast quantity of fossils, which included pre-human species, animal hair, petrified wood, stone and bone tools, and other artefacts.

The President of the Petralona Community gave the skull to the University of Thessaloniki in Greece. The agreement stated that once the investigation was completed, a museum displaying the findings from the Petralona cave would be opened, and the skull would be returned to be displayed in the museum. However, this promise was never fulfilled.

* * *

READ MORE: Graham Hancock: Ancient Civilization Wiped Out By Massive Comet 22,000 Years Ago

Ancient Origins: These 4 Ancient Civilizations Existed On Earth Long Before Human Race

Telegram: Stay connected and get the latest updates by following us on Telegram!

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Collective Spark Story please let us know below in the comment section.